by Matthew Kaemingk

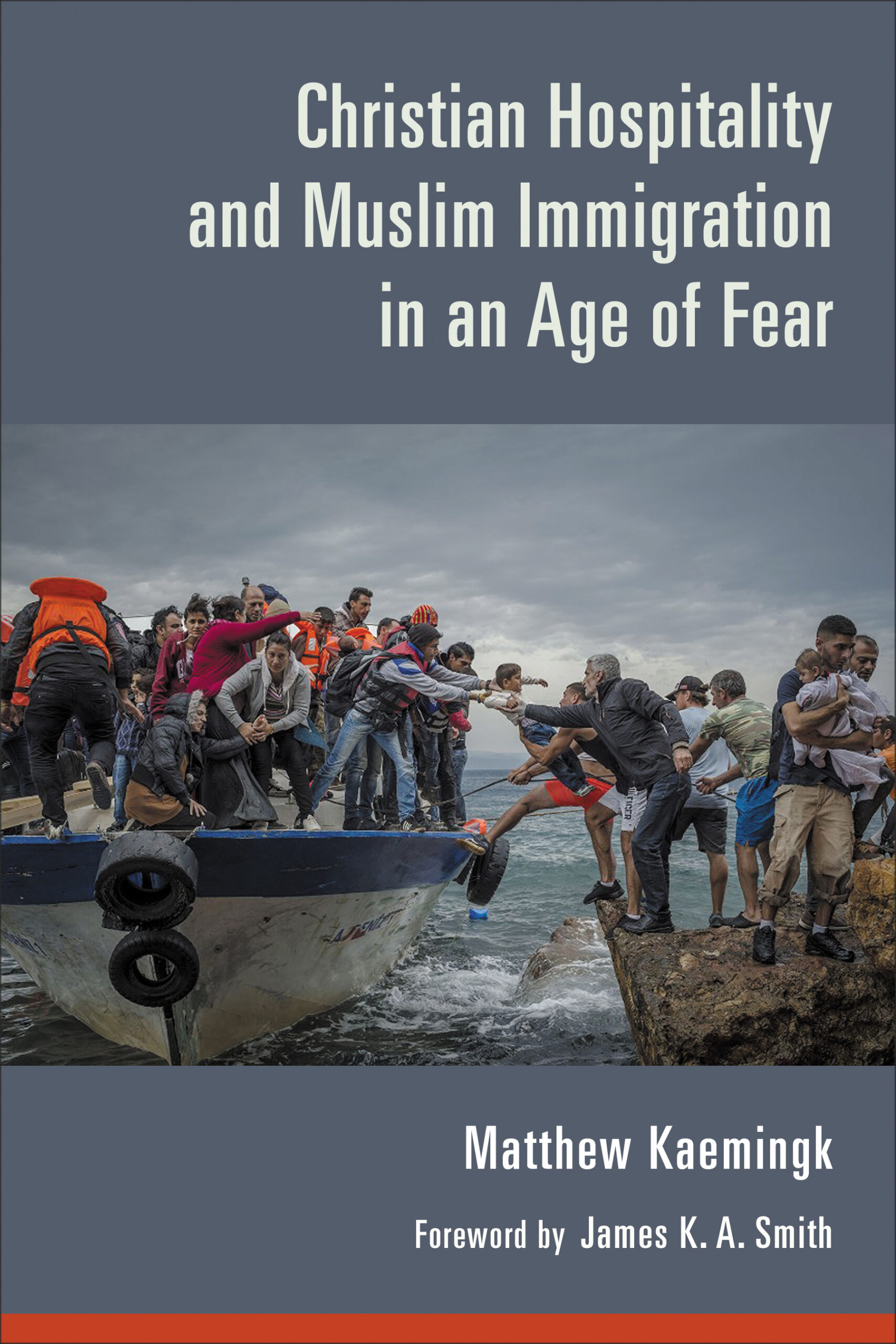

Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. 2018. 352 pp., paper. $28.00.

This review was originally published in Missiology: An International Review, July 2019.

A recent and unique Christian response to the growing Islamic presence in the West deserves the attention of the church. Matthew Kaemingk, Professor of Christian Ethics at Fuller Theological Seminary, writes from the context of the failed policy of multiculturalism in the Netherlands for application in North America. He critiques two major responses to Islam, described as “the antagonism of right-wing nationalism or the romanticism of left-wing multiculturalism” (2). He asserts that in Europe, Islam’s marginalization contributed to extremism and terrorism “through a sense of fragmentation and displacement” (228).

Kaemingk’s goal in addressing the Islamic challenge is to provide Christians “an outside perspective, a fresh approach, a different angle—one that actually emerges out of their own Christian conviction” (4). He invokes Abraham Kuyper’s (1837–1920) view of Christian pluralism to address and alleviate fear and suspicion in encounters with Muslim immigrants. Pluralism is not used theologically as found in soteriological debates concerning ultimate destinies. Rather, he explores the question, “How should Muslims be treated while they are still alive?” (15). In his answer, he maintains “an uncompromising commitment to the exclusive lordship of Jesus Christ” and “an uncompromising commitment to love those who reject that lordship” (16).

Kaemingk contrasts Christian pluralism with four other responses—assimilation, moderation, retreat, and retribution. He believes that the goal of a Christian response to Muslim immigration permits Muslims to practice their faith in the public sphere of life alongside other religions where Christians engage “their diverse neighbors with ‘persuasion to the exclusion of all coercion’” (125). He calls Christians to see Muslims as created in the image of God and to serve them for the sake of Christ. He boldly advocates that “Christian disciples must make hospitality, not justice, the primary frame through which they understand their public and political obligations toward Islam” (186). Lest anyone misunderstand his call for hospitality as utopian, he affirms that “the hospitality of the cross is neither soft nor permissive. It does not appease, it is not naïve about worldly violence, nor is it incapable of defending itself . . . Terrorism must be punished and justice must be executed if hospitality endures” (187).

This book should enjoy a wide reading by church leaders to educate members on this pressing issue and by students of Islam to better understand the dynamics of engagement as the people of God to a people in need of the gospel.